More than 13 million Americans served in World War II. Each soldier or sailor played a tiny part in that historic cataclysm. Dad’s time in that war had such a profound impact on him that those close to him, his wife and children, were deeply affected as well. The effect of those experiences has been passed down to us like any other genetic marker.

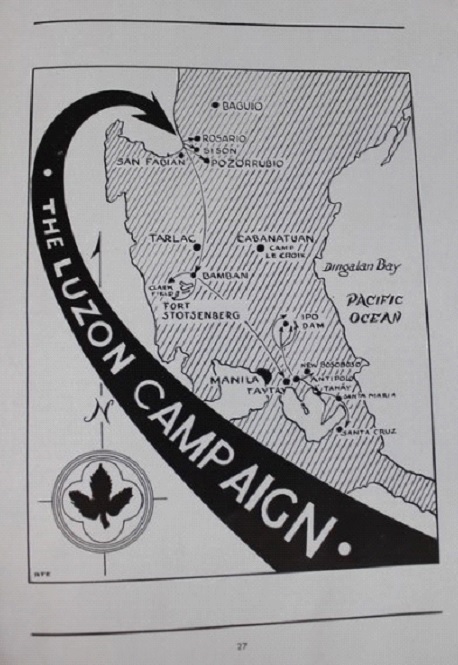

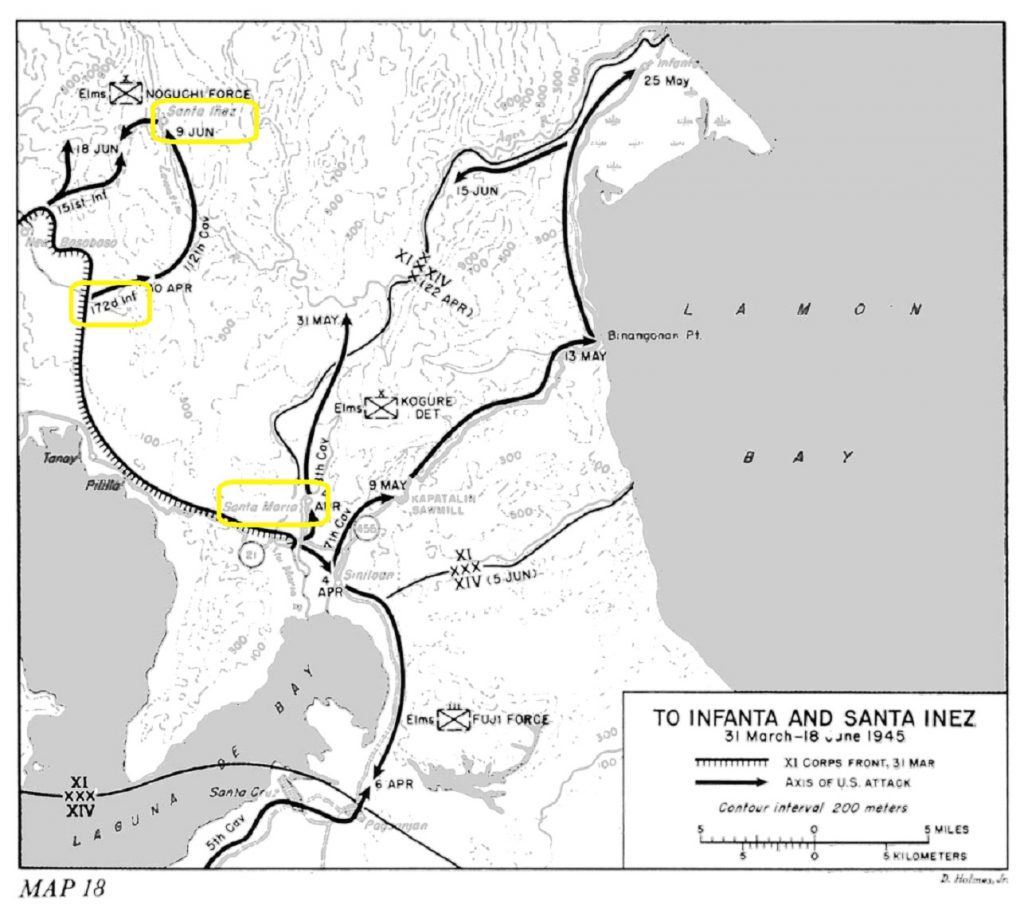

In May 1945, Dad was in the 43rd Infantry Division, fighting in the jungles of Luzon in the Philippines. He played a significant role as the 43rd decimated the defensive lines of the Japanese Shimbu Group which had held the North and central sections of Luzon Island. The success of the 43rd in the campaign to take the Ipo Dam broke the back of the Japanese military.

In 2001, 55 years after he was discharged, Dad gave a statement which led to the Veterans Administration acknowledging that he had suffered Post Traumatic Stress Disorder as a result of his experiences during the war. Here is an excerpt from that statement.

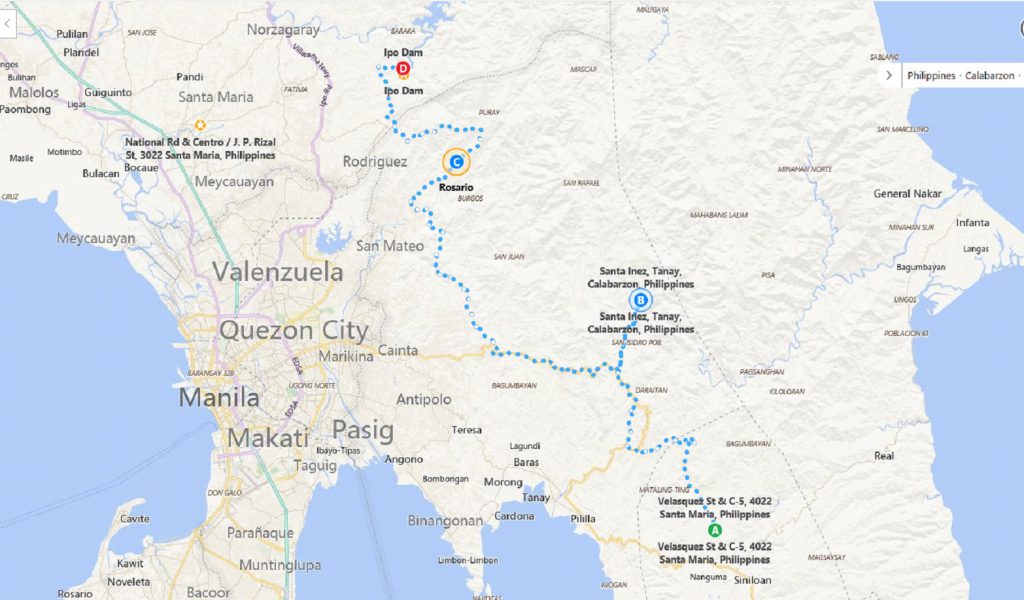

I was involved in the Philippines in 1945, in three major campaigns there: Santa Inez, Santa Maria, and Santa Rosalia.

I used to be exposed to a lot of this killing. Us foot soldiers were on the front lines. We saw everything. We saw grenades, bombs, guns, etc. There was constant shooting all the time… a lot of GIs, foot soldiers, they perished. You know, they were slaughtered. It was just the mines, and their guns and so forth. I was right in the thick of it because I had the firepower. There was fighting and shooting at night, but mostly during the day. It was very involved, so many little involvements that developed every day.

We would take over the little knolls, the little villages and so forth. And during the process of taking over those little places, we would set up the machine guns to protect us from the Japanese who were trying to retake that position that we had. The colonel would locate his defense at locations where we could have our machine gun nests. I had the job of detecting any kind of advance that the Japanese wanted to make to take back the hill that we were holding. And I had to protect what we already had taken over.

The actual fighting was on these wild terrains that were not developed or anything. There were no roads or streets or anything, they were just little trails that lead to the villages that the Japanese were occupying. In the process of doing that, I became more or less involved in reading the terrains, how to take shelter in case we got a “run back” by the enemy. With the Japanese, you weren’t fighting with children, they were very good fighters. The enemy sometimes was able to penetrate our line so the idea was to find out and read the terrains so that we had a way of fighting and also a way of escaping. You want to remember that your best friend in combat is mother earth because when the enemy is shooting at you and you can hide, that’s what you want to do.

When it was dark, that’s when it was most dangerous. The Japanese would use the darkness to sneak back to try and retake the hills. We had to hold onto what we had already taken. And that is where I came in because I had the firepower because I had the Browning Automatic Rifle.

Being involved with BAR, you have a lot of so-called activities to perform and it’s very involved, you have to be a scientist, really, to learn how to handle the terrain and take shelter and you think, “I wonder if I can slide down low enough so that I can operate the way I am supposed to without having to get shot.” The enemy is not stupid; they know what they are looking for. And of course, they want to knock the BAR out of the way, and that is why I was supposed to stay alive and also keep my helpers alive and provide the support that they needed.

And when I had my buddies, both of them got killed, they were the ones that carried my ammo. That was part of the program, I couldn’t carry the gun and carry the ammo too because it was too heavy and too cumbersome. One of my buddies was hiding in a tree, about 20 feet away from me, he was trying to protect himself and I saw the Japanese shoot him. I was hiding in a foxhole at the time. That was very sad. The other one got killed in combat, on the battle-field just a few feet away from me. He was trying to hide because there were a couple of Japanese within range of him and he didn’t want to get killed. The Japanese shot him too. When my friend got killed on the battlefield, I was shooting back at the Japanese.

I saw a lot of people get killed. It was terrible. One time, one of my buddies was eating and he thought he was sitting on a log but when he looked down, he saw that he was sitting on one of the dead bodies of a Japanese soldier. Yeah. (Long silence.)

It was very, very gruesome I would say because there were so many dead bodies of Japanese soldiers and also Filipinos that were all over. The dead bodies just happened everywhere. We used to have to haul dead bodies away and burn or bury them so that we wouldn’t have that stench and also because they just wanted to get rid of the bodies far enough so they wouldn’t be a nuisance because it is very, very sad to see those bodies just laying around so you usually wanted to get them out of your way.

A lot of these things that were very, very – ah – put you in a state of mind where you just blank out. You couldn’t even concentrate. Some of the fellows would just start moaning from fear. Sometimes they would get a shot or they would get this or they would get that to kind of quiet them down. I did the same thing a couple of times where they took me and gave me a couple of shots.

We were glad when we finished that campaign.

After the US capture of the Ipo Dam at the end of May, 1945, the Japanese army was physically and mentally defeated and the fanatical orderliness of the Japanese military could no longer be maintained. During the month of June, the 43rd was engaged in the dangerous job of clearing out remaining units of Japanese soldiers who continued disorganized hostilities in pockets of resistance throughout the Philippines.

During breaks in the action, the men would entertain themselves playing poker. Dad was a pretty good poker player and with a little luck, he managed to pull together quite a bundle of cash. He sent the money home to Mom with instructions to buy some land for a future family home.

When the money arrived, Mom, who was just 22 years old at the time, had been in the country for barely five months and didn’t know a word of English. Just navigating life in this new country was difficult for her. She tells the story of going to a soda fountain carrying my older brother, Tony, who was 11 months old at the time, to order a cup of hot chocolate. The waitress was never able to understand Mom’s Spanish pronunciation of the simple word, “chocolate,” so she had to leave without being served. So, the thought of buying a parcel of real property was even more daunting.

She was living at 504 3rd Av. Redwood City, with her mother-in-law, who didn’t speak English either though she had been here since 1913. At least Dad’s 16-year-old twin sisters who were born and raised here were native English speakers.

Meanwhile, back in the Philippines, on July 1st, the 43rd Infantry Division was relieved of combat duty after 175 days of continual offensive combat. The division moved to Camp LaCroix near Cabanatuan for rest and relaxation. The soldiers who made it to LaCroix were exhausted and many were suffering battle fatigue.

Back in Redwood City, Mom, grandma and my aunts Pat and Angie were eager to follow Dad’s orders so off they went, the four of them in search of the perfect piece of property. At that time, there were just 12,000 inhabitants in Redwood City, so there were plenty of vacant lots everywhere. They managed to find a 75’ 100’ lot on Redwood Avenue in Redwood City selling for $500. They purchased the property on July 10, 1945. Later, the street names were changed to honor our military leaders, so Redwood Avenue became Douglas Avenue and the next street over became MacArthur Avenue.

In late July of 1945, the 43rd Infantry Division learned of its next mission. They were ordered to commence preparations for the invasion of the Japanese mainland. There were estimates that we would lose one million men in a ground assault of Japan. There was plenty of free time for the men to contemplate their fate. It was a time of high tension and all-consuming fear.

Then, on August 6, 1945, a fateful day, the United States, under orders from President Harry S. Truman, dropped an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima. Ninety percent of the city was destroyed, instantly killing 80,000 men, women and children. On August 9, we dropped a second atomic bomb on the city of Nagasaki, Japan. On August 15, Emperor Hirohito announced his country’s unconditional surrender in World War II in a radio address, citing the devastating power of “a new and most cruel bomb.”

Following the surrender, Dad was in the first infantry division to land at Yokohama Harbor for the Occupation of Japan. He was assigned to be a military policeman at the Tachikawa Airfield, Japan’s biggest military airbase. After experiencing the brutality of the Japanese Imperial Army, he was surprised by the courtesy he was shown. He described how the Japanese would turn to salute him wherever he went to show their obedience as a vanquished people at our mercy. He learned to speak Japanese during his year-long stay there.

It’s an unsettling thought today that anyone could celebrate the killing of so many innocent civilians, but at that moment, the whole world changed. The war was over. The killing and brutality were over, but for some soldiers, the trauma of combat never did go away. President Harry S. Truman was revered and honored in our home. My parents believed that his decision to drop the bomb saved Dad’s life.

The line of control on the Island of Luzon, Philippines, on March 31, 1945 and the lines of attack April through June.2018 Google Maps showing a walking route from Santa Maria to Santa Inez and to Rosario, the locations described by Dad in his statement to the Veterans Administration.

⦁ PHOTO ESSAY: THE WAR AND AFTERMATH

World War II was a time of the most profound change in human history. Everyone alive at the time was affected. There was great uncertainty about the outcome of the war. When the US entered the war, the Axis Powers were dominant and there was real fear that they would prevail.

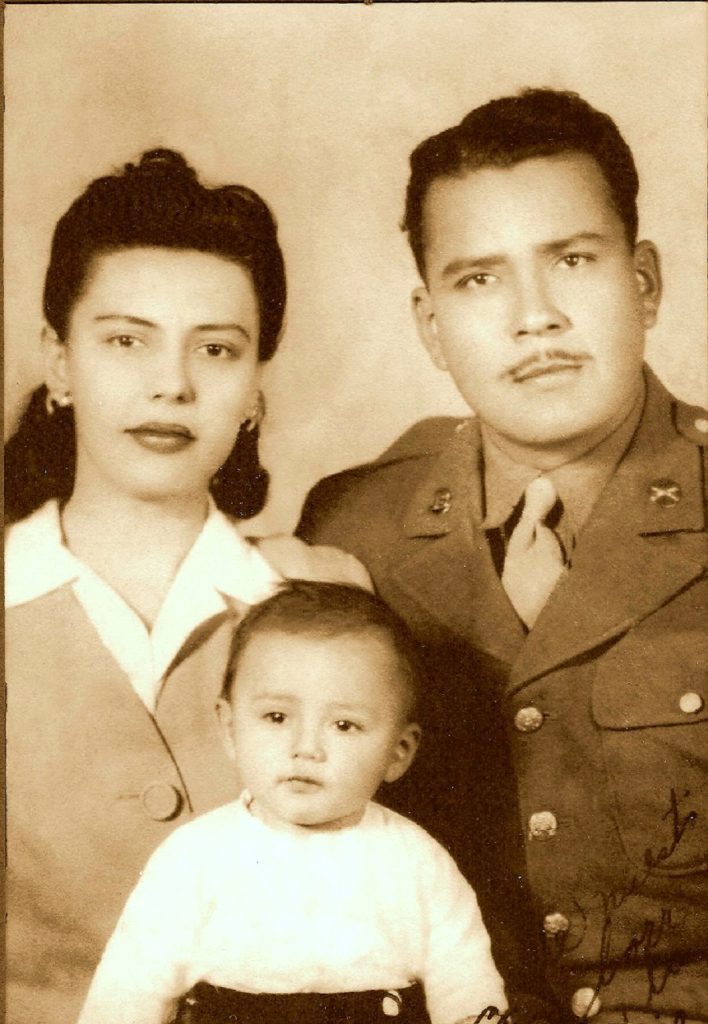

Dad was shipped off to join in the battle for the Philippines. He engaged in three campaigns there as a point man for his battalion and carried the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). He was awarded the bronze star for bravery in battle.

During the fighting he experienced extreme trauma from what he saw and what he had to do. He never spoke of what he experienced during the war. It’s something he kept deep inside. On two or three occasions he recounted how some soldiers were last seen shaking from fear in their bunks at night and were found dead in the morning. Implausible as it may seem, he insisted it was a fact that men died from fear.

Mom always reminded us how Dad returned from the war a changed man. He had developed all of the classic symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): fits of anger, hostility, nightmares and difficulty with interpersonal relationships, to name a few. Although he was highly competent and respected in his job, and had risen to the position of superintendent on major construction projects toward the end of his working life, he had to retire at age 50. He always said his nerves were shot. He would go to the doctor for his hay fever that he developed after the war and his blood pressure was through the roof. His doctor told him to take it easy.

Photo 2.

This photo was taken in April 1945, the night before Dad shipped out to the Philippines. I’m sure he had had a few drinks by the time this picture was snapped. He’s trying not to think about what tomorrow will bring. She’s holding on to him for what might be the last time.

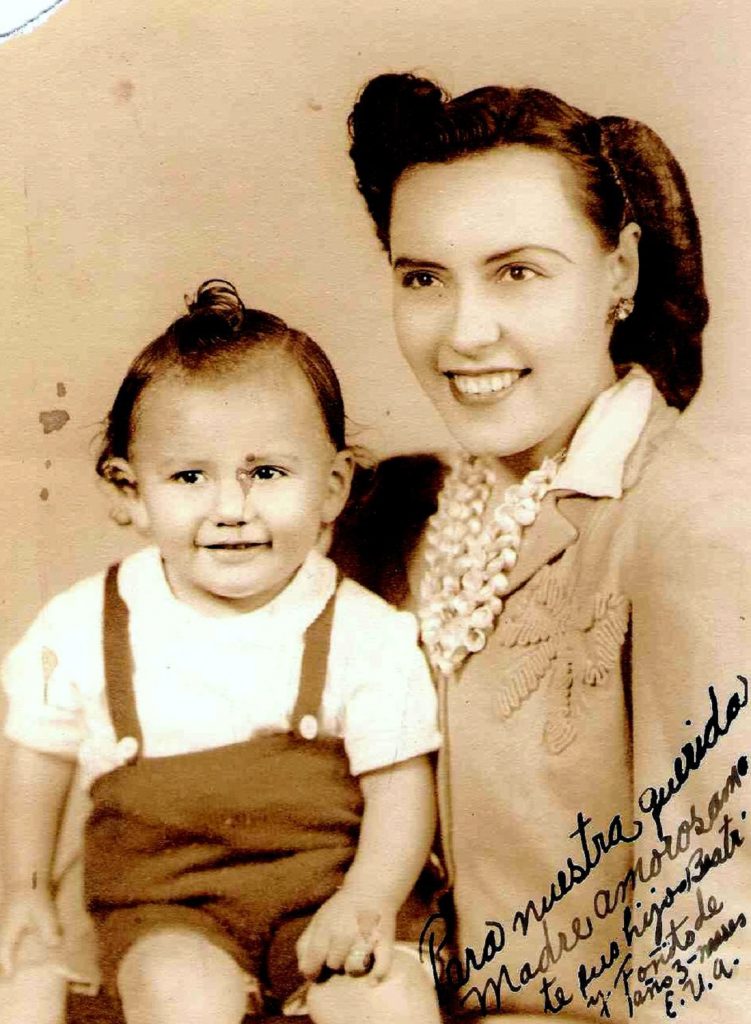

Photo 3. This photo was taken in October 1945, just weeks after Japan surrendered to end the war. Mom’s expression is one of relief that the war was over and that her husband had survived. She sent one copy of this photo to Dad in Japan, and this copy was sent to her mother, Mamacita, in Mexico.

Photo 4. This photo was taken in Japan during the occupation. Dad, on the left, is relaxing with one of his buddies. He looks like he’s in command. His posture is confident and forward leaning. This photo captures the man as I knew him growing up. He was a big man, strong and powerful. He had a commanding presence in any group of men.

Photo 5. Dad was honorably discharged and returned home in November 1946. This photo was taken about five years later.

Body language tells everything. Dad looks tired and angry. He isn’t talking or even acknowledging the photographer. He’s leaning away from Mom and won’t touch her. She doesn’t look happy either but is trying to be present for the camera. Mom would tell us how Dad had returned from the war a different man. Gone was the charming, loving and courteous man she married. He was haunted by night terrors and frequent rages.

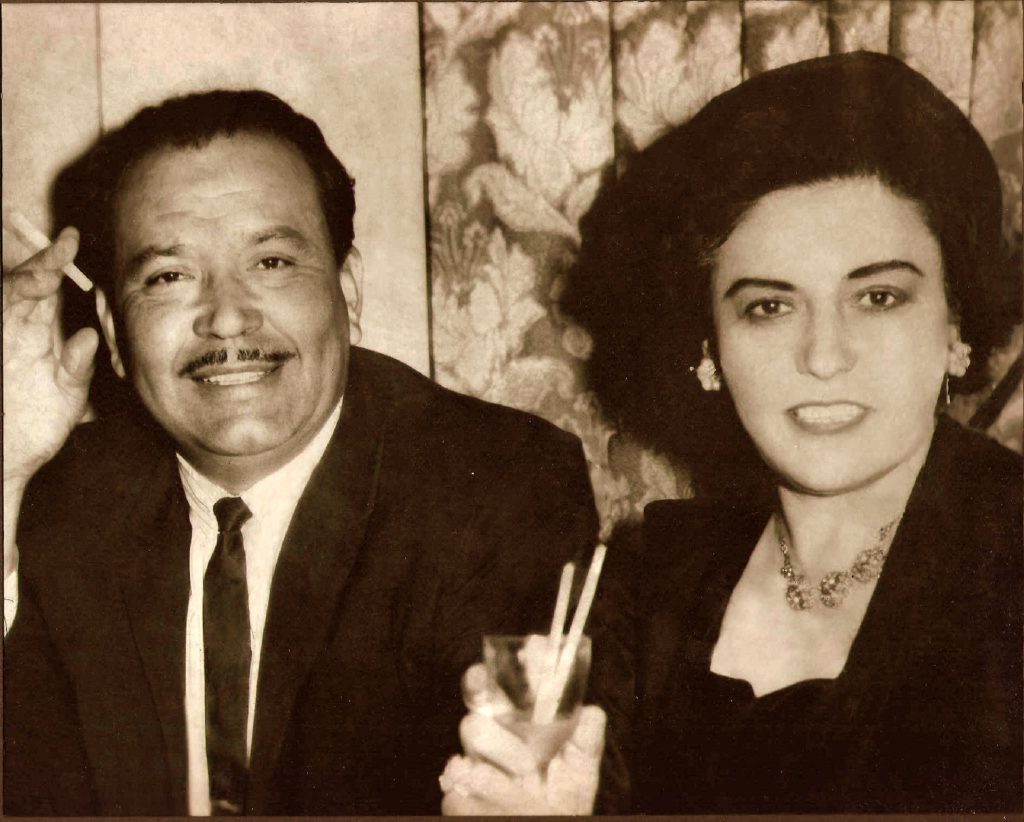

Photo 6. Here are my parents on a night out about 1962. They’re having a good time. That was so important to us kids. It’s how I want to remember them. Dad was an extrovert and charismatic. He could charm and be the center of attention at any gathering.