My family had already settled in Redwood City when I was born, so I gave little thought to the story of how this came to be. Given my family’s history, I might have been raised in Culiacán or Agua Prieta Mexico, or Douglas AZ, or Tucson, or maybe Victorville or LA. This is the story of my family’s history and how we came to live in Redwood City. It turns out my good fortune starts with the turmoil of the Mexican Revolution and culminates during World War II.

The Long Lost Galaz Clan

Even before the Mexican Revolution, Dad’s father’s family, the Galazes were the first to arrive in the US. Dad’s father, Antonio Galaz, my grandfather, was born June 13, 1897 in Magdalena, Sonora. From there the Galaz family moved to Cananea, where the copper mining industry was starting up. The mines were in the hands of Americans and the exploitation of Mexican natural resources by foreigners with the complicity of the Mexican government of President Porfirio Diaz was the seed for the Mexican Revolution. Many of the men working in the smelting plant there were Americans. In 1902, when the Copper Queen Smelting Plant opened in Douglas Arizona, many of the men, including Great Granddad, Antonio Galaz, Sr., his wife, Armida Acosta and children moved there. Imagine, Armida Acosta had 16 children, all but four of whom died in early childhood. Great Grandad Galaz was born in 1871, during the presidency of Benito Juarez, who famously ordered the execution of the Hapsburg Emperor of Mexico, Maximilian I.

Dad’s father was just five years old when he started school in Douglas. In September 1918 Dad’s father was 21 and had to register for the draft. His registration card lists his occupation as Oiler at the Copper Queen Smelter. It also states that he had not “lost an arm, leg, hand or eye,” so he was good to go.

Dad’s mom, Maria Eulalia Quintero, (Grandma) was born in Culiacán, Sinaloa on May 28, 1892. Her mother died when she was 12 and she moved in with her aunt, Efrena and cousin, Antonia. The cousins were together through their teenage years and they both worked as seamstresses.

In 1911, the Mexican Revolution broke out and over the next five years there was fierce fighting throughout Northern Mexico, especially in the State of Sonora and down the entire Pacific Coast of Mexico. Though no battles were fought on the streets of Culiacán, no one at the time could know that battles would not rage there as well. For a time, Pancho Villa and his army camped just outside Culiacan and Mamacita (my maternal grandmother, Antonia Garcia) and her mother cooked and made tortillas for them.

In 1913, Grandma (my paternal grandmother, Maria Eulalia Quintero Gonzalez) joined her brothers Juan and Fabian, who had decided to leave Culiacán and head for the United States for safety. Grandma was an adventurous soul and relished the excitement of leaving her hometown. On July 23, 1913, they arrived in Bisbee, Arizona where mining jobs were plentiful. The Copper Queen mine in Bisbee was hiring anyone willing to work.

Grandma and brothers relocated to Douglas where the main smelting plant was located. There, Grandma met her one true love, Antonio Galaz, a healthy, handsome 21-year-old. After a short courtship, they married on August 29, 1918 in Agua Prieta, Sonora, Mexico.

Within four months, on December 27, 1918, her beautiful husband died suddenly of the Spanish Influenza, a pandemic that killed 50,000,000 people that year, leaving poor Grandma enceinte .

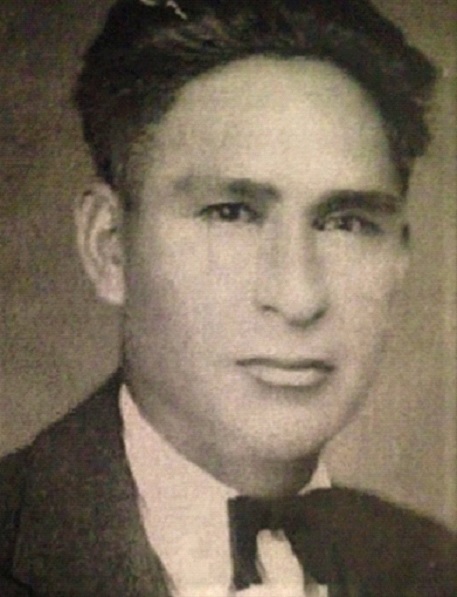

Grandma stayed in Cananea with Galaz family members through her pregnancy. Dad was born on May 10, 1919, and the civil registry of births for the State of Sonora records his given name as Antonio Galaz.

When Dad was one year old, Grandma brought him to stay with her brother, Juan, in Gilbert, AZ, near Phoenix (10/6/1920). Over the next few years, Grandma moved between Cananea, Phoenix and Tucson, but they made Arizona their permanent home and Grandma lost touch with the Galaz family and never had contact with them again.

Tio Juan

Juan and his wife Angela had a daughter, Helen, five years older than Dad. Dad stayed with them when Grandma would leave to find work. Dad was raised in his uncle Juan’s household and they became his family.

Dad attended school in Arizona and since everyone in his household was a Quintero, he never used the Galaz name. While living in the United States, Dad has always been known as Anthony Quintero.

Dad was never one to talk about his past; he was always focused on today. As a child I didn’t even know that Dad’s birth name was Galaz. I didn’t hear the name until much later when my aunt Angie mentioned it. I thought it was a strange name. I didn’t know anyone by that name. I still have not met another person named Galaz. As I did more research, I found that Galaz is a fairly common name in Douglas AZ and surrounding area. It is also found in Agua Preita and Cananea and into the Sierra Madre Mountains to the East.

Juan was a simple unskilled laborer and took any kind of job he could find. Sometimes there were long periods when there was no work to be found. Juan took jobs in mining and smelting; he worked in a steel plant and a cement plant; he worked in a rail yard, did construction work and picked cotton. There was no air conditioning and some places in Arizona have an average high temperature in July of over 100⁰.

The family suffered hardships and poverty, so Dad was just one more mouth to feed. He said he felt like an orphan growing up. Family lore has it that as a child, Dad built a makeshift shelter made of corrugated metal for the family to live in.

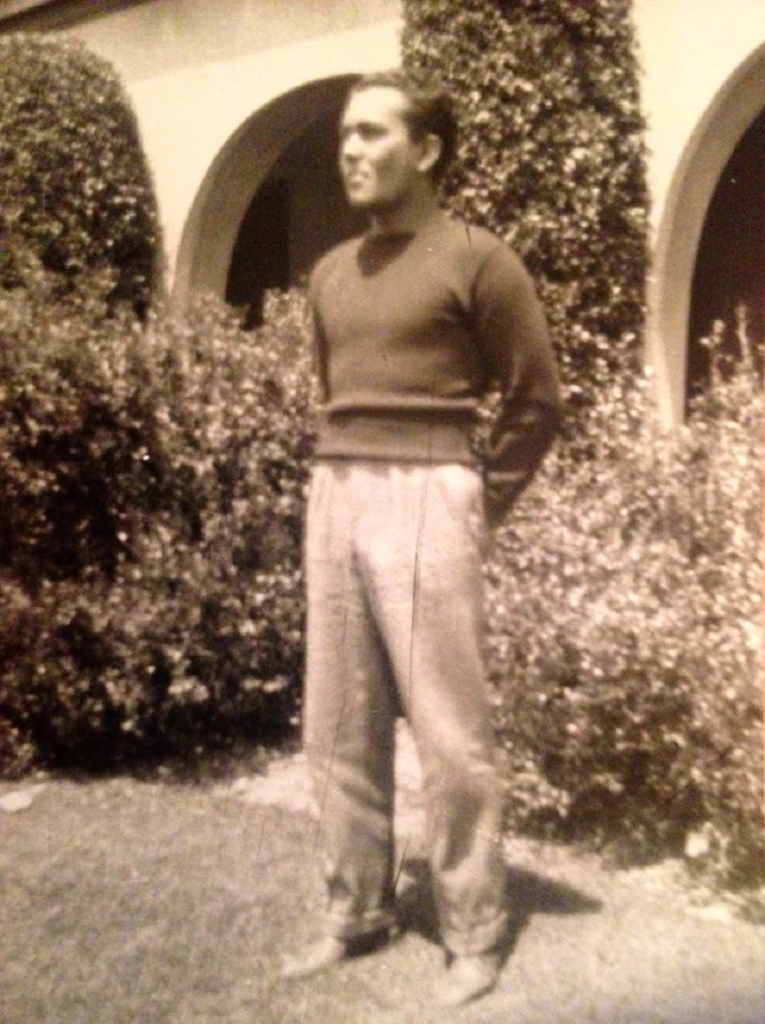

Dad in Los Angeles

Dad and his family moved to Los Angeles in the early 1930s and he lived there from the time he was 13 until he was 24 years old.

The family was struggling in the middle of the Great Depression when they moved into an apartment on Sunset Boulevard, in the center of Los Angeles. Work was scarce and there was lots of competition for every job, but Dad was always a hustler and managed to find work while other men were standing around complaining. As a teenager, he got a job at the famous Brown Derby Restaurant in Hollywood.

In the summer of 1935, Dad was 16 and wanted to join the Civilian Conservation Corps, CCC. It was an easy way to earn money for the family during the depths of the Great Depression. Problem was, he didn’t have papers and minimum age for the Corps was 18. He wasn’t about to let anything so trivial stand in his way, so within a couple days, he had his freshly minted documents and joined the CCC for the summer. His US identity since that day became Anthony Quintero, born May 10, 1917 in Phoenix Arizona, while his Mexican identity remained Antonio Galaz, born in Cananea, Mexico in 1919. It wasn’t until 1951 when Mom was applying for US Citizenship that he obtained a birth certificate reflecting his US identity.

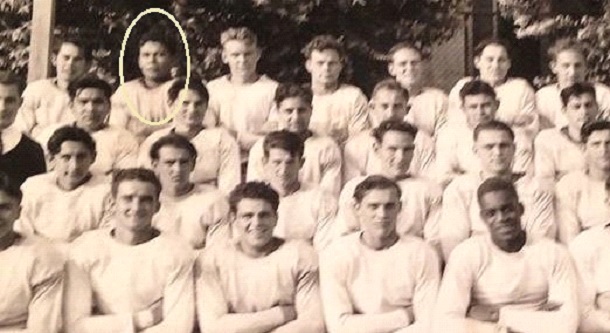

He was a star athlete in high school in baseball and football. He played on the Lincoln High School football team with Kenny Washington, who was the first black athlete to break the color barrier in any major sport in the US He led the NFL in yards per carry and still holds the LA Rams team record for the longest run from scrimmage, a 92-yard touchdown run. After he retired from football, he played the leading role in the 1950 movie, The Jackie Robinson Story. Dad was also a classmate and close friend of actor Jack Webb, who went on to star in the TV series, Dragnet.

Dad wasn’t able to return to school for his senior year because he needed to work to support his mother and sisters. Eventually, he started working with an older friend, Agustin, who owned a truck. The two started a business, delivering building materials and hauling junk to the dump.

Dad had a several girlfriends during his time in LA. One of them was a girl named Stella and they had a son, Paul. Dad saw his son until Stella married another man who adopted Paul.

Then there was Claire, a Jewish girl from New York who may have been his wife. She was a very pretty blonde with green eyes. In 1940 they were living at the Kay Apartments at 106 E. Washington Blvd. Los Angeles. She wanted to return to New York. Dad visited New York with her but she decided to stay and their relationship ended there.

During the 1930s and 40s there was rampant racism against people of Mexican heritage. Dad was 24 years old and living in the heart of LA while race riots were raging. Dad was not a pachuco and wanted to steer clear of trouble.

If the riots and racism weren’t enough, World War II was in full swing and there was the military draft to contend with and he was not eager to get drafted.

He searched for a more permanent solution. He’d always dreamed of returning to his roots in Culiacán Mexico. He’d heard his mother talk of her cousin, Antonia, whom she’d left behind in 1913 when she came to the US By the fall of 1943, he decided to make the trip. He loaded up his car and off he went on a long and winding journey that would take many days. Dad arrived in Culiacán in September, 1943, to visit his mother’s birthplace and to connect with the cousin his mother was raised with, Antonia Garcia.

Mom and Dad in Mexico

The period of Mexican history in the 1930s and 40s is dominated by President Lázaro Cárdenas and the profound revolutionary changes he brought, breaking up the large land holdings, nationalizing the oil industry, agrarian reform and social justice crusades.

At the beginning of 1943, Mom (Beatriz Xochitl Larrondo) had no idea how life would unfold for her. She was 21 years old and was living in Culiacán, Sinaloa Mexico with her mother, stepfather and half siblings, Francisco (Tio Pancho), Andrea and Mercedes. The sentiment and ethos of the Mexican Revolution was a powerful influence of the time.

Mom came of age during this idealistic and hopeful time. She came from a sheltered and peaceful environ in Culiacán under her mother’s quiet tutelage. Her people were not peasants, they were from the city. They were tradesmen and merchants. Her mother’s father had been a zapatero and Mom’s father, Agustin Larrondo, was in the import/export business, shipping sugar and coffee from El Salvador to San Francisco. Later he owned a glass factory in Mexico City. Mom chose a teaching career and she identified as a teacher throughout her life. Her friends, relatives and classmates became doctors, lawyers and businessmen. They were educated and were creating a new Mexican middle class.

One day in the fall of 1943, a tall, dark and handsome young man appeared at the door. He was impeccably dressed in a coat and tie and introduced himself as Antonio Galaz Quintero, son of Mamacita’s cousin Maria Quintero. Mamacita was pleased to meet him and introduced him to her daughter, Beatriz. Mamacita asked about her cousin, Maria’s life since she left home more than 30 years before and reminisced about her teenage years when she and her out going and adventurous cousin, Maria lived together.

Mom was struck by this elegant and charming man who spoke of his life in the United States and the city of Los Angeles California. These places seemed far away and almost mythical to her.

Dad was struck by her beauty and youthful joy. Her complexion was clear and innocent. She was bright but coy. He was mesmerized and his eyes met hers over and over again that evening as he stayed for a celebratory family dinner and they talked and laughed into the night.

Before he returned to the Hotel Durango that evening, Mom nervously offered to show him around town the next day if he wasn’t too busy. His eyes opened wide as he happily agreed to return for her in the morning.

The next day he called for her at her house and both of their hearts were fluttering. They slowly strolled to the town square, accompanied by Mom’s little sisters, Andrea and Mercedes. The two were inseparable over the next month. Meanwhile, Dad’s head was spinning. He was falling in love with his beautiful second cousin and thinking about starting a new life in Mexico. He imagined new businesses he could start; the opportunities seemed limitless. Mom was awestruck too. She was dreaming of faraway places like Los Angeles and New York. Everything else in her world seemed to shrink in importance compared to the dreams this man had sparked in her.

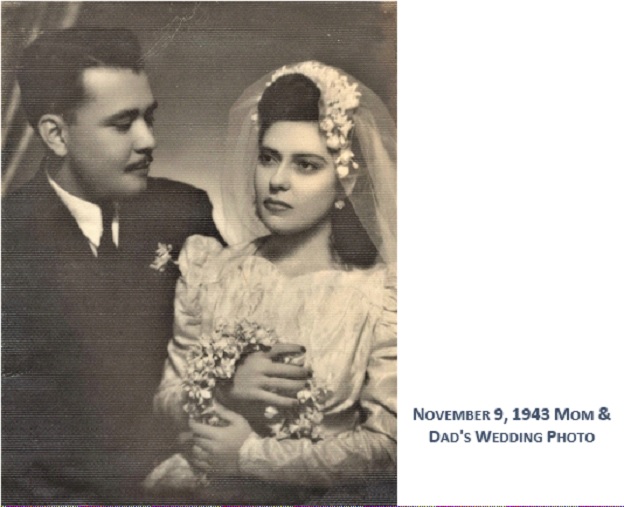

With his heart bursting, he asked her to marry him. Without giving it another thought, she said yes. And so, Antonio Galaz and Beatriz Larrondo were married, November 9, 1943, in the city of Culiacán, Sinaloa, Mexico.

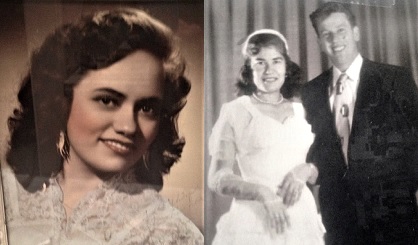

I’ve spent hours staring at Mom in her wedding photo, wondering what she was thinking. She has a faraway look. She’s serene, not exuberant, not smiling. She’s thinking, wondering. She doesn’t know what the future may bring. She hadn’t known him long. They were second cousins.

“¿Es este el fin de la vida que he conocido? ¿Que será mi vida en el futuro? Voy a extrañar a mi mamá, a mis hermanitas, a mi hermanito Pancho. Tendré que dejar mi carrera como maestra. Hay tantas cosas, tantas cosas, tantas cosas…”

After the wedding, Dad started planning his next project. There was a severe lumber shortage during the war years and Dad hoped he could make a killing importing adobe bricks from Mexico. He spent some time researching how to make adobe brick and looking for the right location to build a brick fabrication plant. Mom spoke of her friend, Licha who had married into a wealthy family, the Garibaldis. They decided to go for a visit to announce their marriage. It was a long drive, about 150 miles North to the city of Los Mochis and then East, following El Rio Fuerte beyond Charay up a rugged unpaved road to the next little village, San Blas, Sinaloa.

The Garibaldis owned a large hacienda there. Dad discussed his plan with the Garibaldi family and was persuasive. The brick fabrication would take place on the Garibaldi hacienda, using the natural soils there and Dad would advance the capital, know-how and management to bring it to fruition. They agreed to share the profits of the venture.

It was a perfect location, plenty of clay, silt and sandy soil, sun and water. There, Dad had learned of a process for making a harder and stronger adobe brick, called quemado, which requires firing sun-dried adobe at a constant temperature. The kiln would be built with the adobe to be fired. He put all the workers from San Blas and the surrounding area to work on the project. The entire village became involved in the project.

Mom was well along in her own project. She was pregnant and the hacienda was no place for a delicate young pregnant woman, so Dad agreed that she could go visit her best friend, Maria Encinas, who lived in the modern city of Ciudad Obregon. At that time, Maria Encinas’ husband was a telegraph operator but he had higher ambitions. They promised to take good care of Mom while Dad was working in San Blas.

While the laborers were still forming bricks, Dad had to take time away from the project as he received word that Mom had given birth to their first child. Dad traveled to Ciudad Obregon, about five hours away by vehicle over rough roads to see his son and to be at her side. When he saw his beautiful newborn son, he and Mom agreed to name the boy, Marco Antonio Galaz.

When he got back to San Blas, the brick kiln was ready to be fired. The most critical elements in the process are the composition of the adobe which must have the right mixture of clay, sand and silt and the temperature of the kiln, which is the most difficult to control.

They fired the massive kiln with wood and let it burn for a day. As the kiln started to cool, everyone gathered around to watch, the Garibaldis, the workers and their families and other towns people. As the fires burned out and the summer breeze blew through the kiln, small cracks started to appear in the brick. Soon the cracking of the bricks became audible and the crowd was murmuring. Sections of the kiln began to break off, and the kiln walls began to crumble, until the entire kiln collapsed into a pile of rubble. Along with it, Dad’s finances and dreams for the future collapsed

Los Quinteros to America Part II

Without funds to continue, Dad looked for a next step, as he was now responsible for a wife and child. He decided to return to the US to raise money or devise another plan, while Mom and their newborn returned to Culiacán to be with her mother. The failure of the kiln led to Dad’s fateful decision to return to the US and marks the pivotal moment that changed the history of generations of present-day Americans.

When Dad got to the US-Mexico border, he was an American again and showed his California driver’s license for identification. On this occasion, for the first time, he’s questioned. The border guards were not questioning his nationality. They wondered how an able bodied 27-year-old man was not serving in the war effort. He was detained and taken into custody. He was given an ultimatum, either accept induction into the armed services, or rot in jail. These were dark days. After the failure of his grand project, the loss of all of his money and winding up in jail, it didn’t take long for Dad to accept conscription into military service. He knew serving in the US Army would cement his status as a US citizen and legitimize his USA identity.

On October 6, 1944 he was sent to Fort MacArthur for induction and to Camp Roberts for an intensive 17 weeks of basic training.

In February, 1945, he was sent to Fort Ord, which was the staging area for fighting units, including the 43rd Infantry Division, who were being deployed to the Pacific Theater to fight the Japanese Imperial Army.

While at Camp Roberts, he wrote to Mom, telling her to come to the US to stay with his mother, who was by then living at 504 3rd Av. Redwood City, CA. He explained the importance of using his American name, Anthony Quintero. He also sent an official document from the US Army supporting the request. Mom obtained a provisional passport (12/15/1944) from the Mexican Government using her husband’s American last name, Quintero and the US Consulate in Mazatlán granted her a visa on January 4, 1945.

On January 17, 1945, she arrived at the border town of Nogales with her baby, her baggage and her documents. She left her things with a friend in the waiting room and passed through to meet with the immigration officer. When the officer saw the official letter from the US Army requesting that as the wife of a serviceman, she should be allowed safe passage, the officer became most accommodating and gracious. The final paperwork was quickly prepared and her passport was stamped, “Admitted Immigrant 4(c).”

She returned to the waiting room to pick up her bags and belongings. Her friend waited for Mom in the ladies’ room with the swaddled baby. They wrapped the baby tightly under her clothes and covered her with a big winter overcoat. Mom carried her suitcase in front of her and quickly crossed into Nogales, Arizona, USA.

Baby Marco Antonio Galaz was not yet six months old at the time, but there is no documentation of his entry into the USA. A few months later, Mom took him to the County Registrar’s office in Redwood City to register his birth in Redwood City, with the name, Mark Anthony Quintero.

And so, history repeats itself at the beginning of the next era of the Quintero family saga. Just as Dad, born in Mexico as Galaz and raised in the US from the time he was one year old, as Quintero, so too was his first son born in Mexico only to be raised in the USA from the time he was six months old.

Every Chicano knows how and when they or their forebearers came to the US, and it would be hard to find a Chicano who does not have an “illegal” in his or her family tree. It’s why we feel insulted when people speak ill of undocumented immigrants.

When I have gardening days, I often head down to Home Depot to pick up a couple of day laborers. Most of the workers are Guatemalan or Salvadoran. I always talk with them about their families in Central America. Many have wives and small children back home. They speak of the heartache of being separated from their wives and hearing their children cry on the phone.

They have stories of hardship and danger on their journeys to the US. The cost of the coyotes is exorbitant, often part of the money is borrowed with their families as collateral. The journey is filled with dangers from bandits and criminals, or the hazards of travel aboard open freight trains. They speak of the dangers at border crossings in the desert. These stories are as harrowing as any story of heroic struggles in the settling of the West; covered wagons crossing over the Sierras; the Mayflower, or in the steerage of the coffin ships during the Irish potato famine.

Mom Arrives in Redwood City

Mom was happy to finally arrive in Redwood City after all the struggles she’d gone through. She met Grandma and the twins for the first time. They were all happy to meet her. Angie said Mom looked like the actress, Linda Darnell.

Life was difficult. There were now six people squeezed into the tiny apartment on 3rd Avenue and there was friction. Given Mom’s life in Culiacán, Dad’s family seemed crude and lacked refinement. There was shouting and swearing that Mom wasn’t accustomed to. To them, Mom must have seemed an uppity prima donna. In time, the friction became epic battles.

Mom built up a resentment that would last her lifetime. She forbade us from going next door where Grandma’s family lived, but we didn’t obey. We’d go over all the time. They treated us with candy and snacks and we’d watch TV and go on outings with them. When we got back home, Mom knew we’d been next door. She said she could tell by the smell. She disapproved but didn’t do anything about it.

Simón Moreno

In 1928, Grandma and Dad followed Tio Juan to Victorville, CA. At that time, Victorville was up and coming. It had an important railroad station and Route 66 had just been built and passed through the middle of town. There was plenty of work available in the apple orchards, mining and cement. There was a huge demand for cement for construction in Los Angeles which was in the midst of a population boom. Dad’s uncles, Juan and Fabian found work at the cement plant.

Grandma liked to go dancing at the local dance hall. She was popular with all the guys there, and they called her “La viuda con ojos verdes,” but the one who caught her eye was the band’s saxophone player, Simón Moreno. In no time, the flirting became serious and they married in San Bernardino, CA in August, 1928. The following year, the newlyweds had twin daughters, Angie (Angelita) and Pat (Petronila).

But when the Great Depression hit, there were massive layoffs in Victorville so Simón went off to Los Angeles in search for work with Grandma, Dad and the twins in tow. Simón struggled to find and keep jobs, so Dad had to pull his weight to keep the family afloat.

In 1939, stepdad Simón found work as a mucker at the quicksilver mines in New Idria, high in the mountains in San Benito County. The following year, Grandma and the twins joined him there. It’s a desolate and merciless place. Dad was never close with his stepfather, so he decided to stay in Los Angeles with his girlfriend, Claire.

In 1943, Simón got a job as a painter at the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard in San Francisco, which was one of the largest ship building sites during World War II, and Grandma and the twins moved to South San Francisco. After a short time, he got work at the cement plant in Redwood City. Simón had a sister, Mary, who rented the family a house on 3rd Avenue.

And so it is that my good fortune to grow up and live the rest of my life in and around Redwood City comes from the misfortune of one man, Dad’s stepfather, Simón Moreno.

Simón didn’t live with the family after I was born. He’d show up at Grandma’s once in a while with bags of groceries. When I knew him, he was a thin man with straight pepper grey hair and glasses. He’d stay a few days and be gone again, looking for work. Dad didn’t relate to him much when he came around. I don’t recall relating to Simón much either. He was interested in Grandma and his daughters. He laughed a lot and seemed to have a good time when he was around. Later I’d heard rumors that he liked to drink.

The Cast of Characters

Dad always had his entourage, and our home became a center for parties and get togethers. My childhood was filled with a cast of characters who created a community with Dad as the center of attention. There were parties and gatherings and guests, a constant flow of people to relate to. My childhood was enriched by that experience.

Grandma and Pat and Angie were part of the community, and so was Simón when he dropped by. Our orbit included Grandma’s friends, like Portela, a pig farmer who always brought gifts and gave us money, and Manuel Ortiz and Felix who were godfathers to me and brother Cesar.

Dad’s “sister” Helen and her husband Ralph Vasquez visited a lot.

I love this 1956 picture of Dad smiling. He was always happy when Helen came for a visit. She was his cousin, but Dad always called her “sister.” He said he felt like an orphan as a boy since he was raised by his uncle Juan. Juan’s daughter Helen, a red-head, was six years older than him and growing up she became his protector. He always loved Helen. I never cared for her much. She had a rough personality and never brought us presents.

Dad met Angelo while studying at Cogswell College in the city after the war. Dad had fun going off with Angelo and they became buddies. Angelo and his wife, Vera, were an odd couple, he was a slightly off kilter Sicilian and she was a very proper Australian. Mom became close with Vera and our families socialized together a lot.

Angelo had been a boxer and was into body building. He got our whole family into physical fitness. We’d do “roadwork,” jogging up Douglas Avenue to Spring Street, through Redwood Village to Middlefield Road and back. We also got barbells and dumbbells so Tony and I could work out. I was fascinated with Paul Anderson, the strongest man in the world.

Pat and Rosie Ryan were regulars at the house. Pat was a wild and hard drinking Irishman and Rosie was a pretty Mexican woman. He and Dad bought a lot together on Sweeny Street in Redwood City where Pat hoped to house his machine shop. It never got built and they eventually sold the property.

Dad’s gambling buddy was Ray Gil, a small wiry guy he called “the joker.” He and wife Mary visited often. Dad and Ray liked to visit the poker clubs. Dad would get pumped up and would brag about his winnings. One day he came home in a bad mood and never went to the clubs again.

Some of the characters stayed with us, like Shorty (Margarito Chaides), a recovered alcoholic who was our live-in gardener until he lost touch with reality and could no longer function.

When Tony Romero came from Mexico, he lived as a boarder in our house. He helped Dad a little when Dad was building the apartments next door and at the end of the day, they’d have a beer together. Mom helped Tony write letters to Carmen, his girlfriend in Mexico and supported his decision to bring her here. Their romance bore fruit. He married Carmen and had lots of kids. Tony later had a restaurant on Middlefield Road. His oldest daughter, Sandra married a cousin, Tio Pancho’s son. It did not end well.

Another tenant, Jack Evans, was an electrical engineer. His apartment was filled with tiny electronic parts. He had two thumbs on one hand. He would show me how he could pinch with the two thumbs. He married Lola in our back yard. She made him have the extra thumb removed before the wedding.

When I was in high school, I became friends with one of our tenants, an old German man, Franz Wieser, who had escaped Germany when Hitler came to power and moved to Brazil. We spent many nights talking and playing chess. He’d tell me stories of his escape from the Nazis and his life in Brazil. I’d practice my German with him and he taught me some German tongue twisters.

Go Forth and Multiply!

Grandma’s decision to leave Culiacán in 1913 was the seminal event that has given birth to generations of Americans with roots in Mexico. She brought Dad to the US when he was 1, then had twin daughters. Dad brought Mom, who brought her brother, two sisters and mother, and so it goes.

We were all pretty well settled in at our homes on Douglas Avenue in the early 1950s; our family at 527 and Grandma and the twins, Pat and Angie, at 533 Douglas. Before long Angie showed up with a young, skinny, fair haired guy, Walt Douthat. I remember once while watching TV next door, Walt and Angie were on the couch and I saw Walt feeling her up! They married and moved to San Jose. Walt was an airline mechanic for Pan Am. They have five children, 11 grandchildren and 16 great grandchildren.

In the 1950s Mom’s entire family eventually migrated to join us in Redwood City. First, Tio Pancho (Francisco Jacobo), came. He already had a large family in Tijuana. Eventually, he remarried and had six more children in Redwood City. Each of their children have also been busy populating the planet. Everyone loved Pancho. He had the most amazing sense of humor. Almost everything he ever said was a joke and could make you laugh. He had a big heart and was always giving of his love. Miss him.

Mom’s sisters, Andrea and Mercedes showed up around 1954 or ’55 and stayed with us. I thought they were both awfully pretty and I fell for Mercedes real hard. Later, whenever I saw Mercedes, we would joke and I’d call her, “girlfriend.”

One day in 1955 some guy on a loud Indian Motorcycle came riding up, making a scene, looking for a place to live. He had just arrived from his family home in Wisconsin. His name was Milton Borg and Dad rented one of the apartments to him at 517 Douglas Avenue. This guy had a definite wild streak. He had a large color tattoo of a naked lady on his forearm. He showed

me how he could make her dance by making a fist and moving his fingers.

I recall an engagement party at our house for Andrea and a guy named Joe, who I didn’t know. There was a scene, there were tears and they broke off the engagement. Milton was always hanging around at the time, and he had his eye on Andrea from the start. Before long, his overtures were too much for Andrea to resist. He proposed, but Andrea would not marry him as long as he had that tattoo. Milton had to get his prized tattoo surgically removed with a skin graft which left a massive scar over his forearm. Finally, they ran off to Reno for a New Year’s Eve wedding.

Milton was a coiffeur and had a highly successful beauty salon business in Menlo Park. He had a way with rich women, and they couldn’t get enough of him. Milton never took a vacation during his entire hairdressing career. He worried that if he took time off his clients might go somewhere else and never come back.

Milton and Andrea moved to a large home in the finest Menlo Park neighborhood where they would raise their two daughters, who in turn gave them 5 grandchildren.

He eventually bought Dad’s two apartment buildings on Douglas, 517 and 511. In 1964 they went in together to purchase an old, dilapidated house on the corner of Alma and Oak Grove in Menlo Park. The city council agreed to change the zoning for the property to commercial and Southland Corporation, the parent company for all 7-Eleven stores world-wide, agreed to be the anchor tenant for the development. Plans were drawn to Southland’s specifications and Dad managed the construction of the three-unit mini strip mall. It was a perfect location for Milton to establish a beauty salon to cater to the affluent ladies of Atherton and Menlo Park.

Mamacita, was the last to arrive from Tijuana, in about 1960, after her husband, Francisco Jacobo, Sr. had died. She stayed with us for a short while then moved in with Milton and Andrea and stayed with them until she died at age 100 in 1996. Mamacita was a devout Jehovah’s Witness, though she was never able to convert a single family member.

Mercedes married Leo Mendoza of San Diego, a veteran of the Korean War. He too became a hairdresser and worked with Milton for many years before opening his own shop. They had three children: Leo Ivan, Elizabeth Tabler with one child, and Olivia Dibert with three. When Olivia was still a teenager, she was invited to tour with MC Hammer as a dancer, but she turned him down.